Will this Parliament Be Better than the Last? The Toxicity of Zero-Sum Politics

As much as politics in general these days is being degraded by social media propaganda and misinformation, narrative warfare stunts and tactical intractability, the precariousness of minority governments can make the political discourse that accompanies them especially toxic. Dalhousie University’s Lori Turnbull explores the possibilities for a more civilized tone.

Lori Turnbull

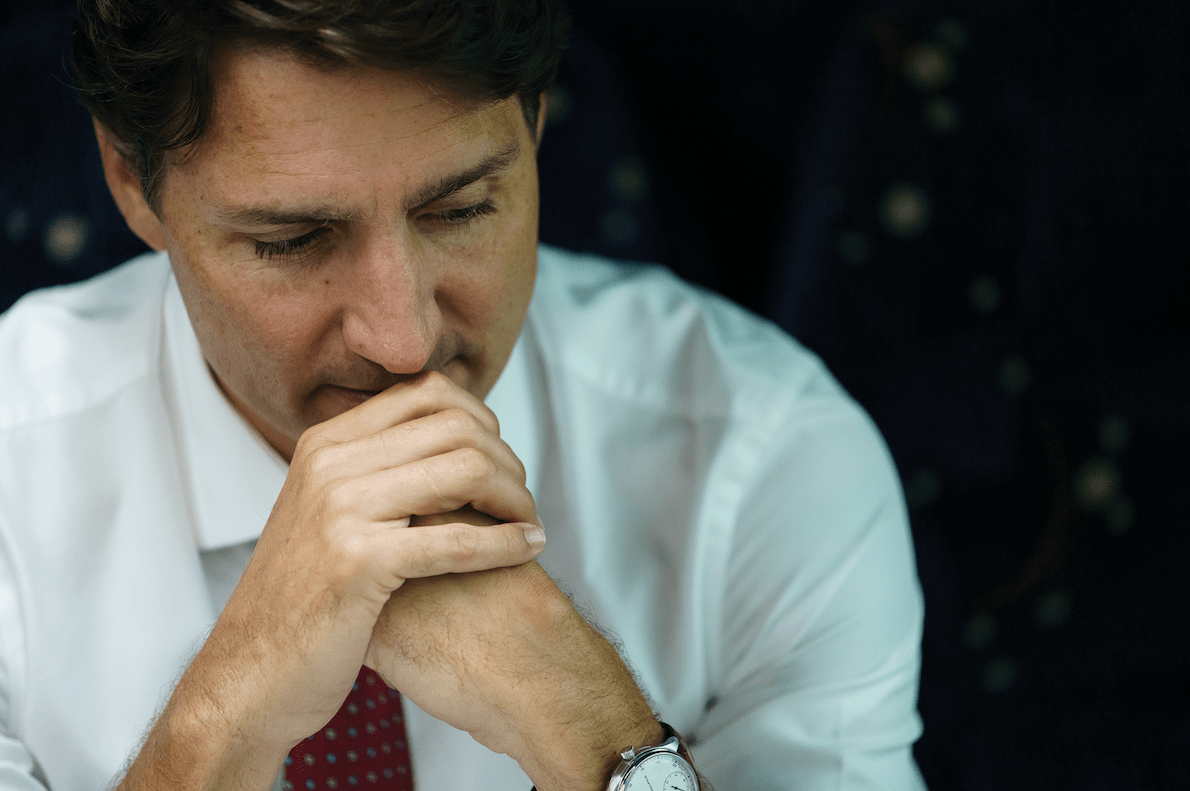

Since In June of 2021, as Parliament was winding down for the summer, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau escalated the already-rampant election speculation by observing that the House of Commons had become a place of “obstructionism and toxicity.”

In other words, it could not continue. However, the general election of September 20th produced a minority Parliament that looks almost exactly like the one before it. Specifically, the size and strength of each of the political parties remains largely the same. Given that very little has changed, ought we assume that the forthcoming Parliament will be as toxic as the last one? Where does this toxicity come from in the first place? And what can we do about it?

The toxicity in the House is really partisanship run wild. It is the tendency for politicians to prioritize partisan gain over their collective responsibility to govern in the public interest. Rather than working together to manage complex challenges that cannot be solved within a single electoral cycle or by a single government, parties and their leaders demonize one another in the hope of frightening voters away from opponents. Perhaps it is not surprising that politicians succumb to this language on the campaign trail, but it is loud and clear inside Parliament as well, where it has a corrosive effect on our governing institutions.

Committee meetings, for example, are overrun by partisan bickering and accusations of corruption, incompetence, and obstruction, and do not provide a meaningful venue for policymaking and/or government accountability.

The parties see politics through a zero-sum lens: a gain for “them” is a loss for “us”. This mindset prevents any meaningful collaboration or cooperation between parties, even on the issues and priorities that they agree on (this is particularly bizarre). Take, for example, the campaign platforms of the Liberals and the New Democrats in this year’s election. There is far more agreement than disagreement on key issues like child care, health care, and affordable housing—all matters that will require long-term attention and significant public investment to get right. There is so little light between the two parties that some question whether we really need the two at all (this is a fascinating question for another day).

But instead of signalling a willingness to partner on common goals, the leaders accuse one another of being ineffective and untrustworthy. They guard their bases and attempt to score points at the other’s expense. Admittedly, some will respond to this critique by saying: “No kidding, that’s politics. The parties are in it to win it.” Fair point, but this sets a very low bar for the level of discourse that we have come to accept in Canadian politics. No wonder so many people don’t vote.

We often hear praise for minority government periods on the grounds that parties will be “forced” to cooperate to get things done. The truth, however, is that minority Parliaments tend to be even more toxic than majorities. All parties are precarious due to the uncertainty of the situation. Governments itch to purge the place as soon as opinion polls suggest that a majority is within reach. Meanwhile, opposition parties are in reaction mode because the prime minister could trigger an election at any time and will likely do so when the opposition is least ready for it.

The minority Parliament that is about to meet is likely to be more toxic than the last one rather than less because, apart from Yves-François Blanchet, the leaders are all vulnerable. Neither Justin Trudeau, nor Erin O’Toole, nor Jagmeet Singh lived up to expectations in this election. They’ve all got something to prove, so we can expect them all to focus on scoring wins that they can deliver back to their bases. We’ve already heard from Singh that the NDP won’t hesitate to “withhold votes” when the Liberals push forward with legislation that they do not agree with. So, in other words, they will disengage and preach rather than work on a compromise.

Even in the last Parliament, when the NDP provided support to get legislation passed, Singh would usually hold a press conference immediately after a vote to explain that he didn’t really have confidence in the government; he just didn’t want to be responsible for an election. It was as though he wanted to avoid any accusation of being cooperative.

Trudeau’s attitude toward the House is alarmingly dismissive. The new Parliament is not sitting until two months after election day. And when parliamentarians do come together on November 22nd, they will be immediately engulfed in a debate about the pandemic support programs that are set to expire. It is expected that the Liberals will continue their preference of holding fewer sitting days, thereby reducing opportunities for government accountability.

The one thing that makes the upcoming Parliament different from previous minority Parliaments is that triggering an early election is not an option, either for the government or the opposition. No one wants it. Voter resentment of the early election call this summer was palpable throughout the campaign. Whether they like it or not, the parties are stuck with each other in this minority Parliament for a while.

Politicians might choose to carry the toxicity of the last Parliament into this one. Alternatively, they could choose to accept the fact that parliaments are built to last.

Minority parliaments can, in fact, last four years. Sure, bills will take longer to pass and we might see more amendments in the process, but these are not bad things. In the current system, there are three national political parties, each with a solid enough base of support that it would be very difficult for any of them to win a majority of seats, no matter when an election is called, and of course impossible for the Bloc, as it only runs candidates in Quebec. The Green Party has been reduced to two seats in the House, and has bigger problems to worry about than procedural tactics.

Therefore, we need to normalize minority parliaments instead of treating them as temporary. This would likely involve a reconsideration of some of the norms that we have grown accustomed to. For example, it is not helpful to good governance that we tend to treat every piece of legislation as a confidence matter, which means that parties looking to avoid elections end up voting for legislation that they don’t really support.

It is reasonable for governments to lose a vote here and there but continue to govern, so long as there is no doubt about whether the prime minister holds the confidence of the House. It is reasonable and legitimate, also, for government to change hands without going to an election. This is exactly what Parliament is for: to choose a government and hold it to account.

If parties and politicians can accept these not-so-uncomfortable truths, we might be able to mitigate some of the toxicity that Prime Minister Trudeau referred to back in June. But this would require them to suppress the tendency toward the kind of zero-sum thinking that makes good governance impossible. They would need to resist the stunts and rhetoric that make for interesting television but prevent consensus and progress. A shift like this would require good faith and strong leadership.

Prime Minister Trudeau is at a pivotal moment in his career. He has been in the role for six years and most of the last two of them have been swallowed up by a pandemic. If he wants to be a 10-year prime minister who has a meaningful legacy to stand on with respect to climate change, reconciliation, and growing the middle class, he should work with this Parliament in earnest to make progress on these goals.

In so doing, he would not only situate himself as one of the best prime ministers in history, he would bring integrity to an institution much in need of repair.

Contributing Writer Lori Turnbull is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Director of the School of Public Administration at Dalhousie University. She is a co-winner of the Donner Prize for Political Writing.