You Take the High Road, and We’ll Take the Low

By Douglas Porter

April 12, 2024

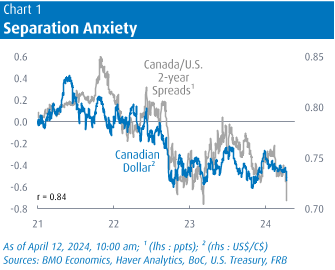

How far can the Bank of Canada diverge from the Federal Reserve? That question was swirling this week, with some serious separation in policies moving from the merely academic to a real-world possibility. Wednesday’s confluence of a third clunky U.S. CPI, and mildly dovish remarks from the BoC soon afterwards, had the markets chattering about a deepening policy divide. In a week that saw U.S. Treasury yields post another big push higher, Canadian short-term yields trailed well behind. Accordingly, the two-year spread has widened by roughly 50 bps in the past two months alone to more than -70 bps (Chart 1). In turn, this has sent the Canadian dollar skidding below 73 cents (or above $1.37/US$), its weakest since early last November.

BoC Governor Macklem was asked very directly about this issue of potentially divergent North American monetary policies, and his response was also quite clear: Canada will do its own thing. We explored this very issue in a Focus Feature late last year (Nov. 10/23); we’d like to think we were prescient, not early, on this file. Some of our key conclusions were:

- Of course, the Bank of Canada can diverge from the Fed. A look back over the past 50+ years reveals plenty of periods of sometimes wide divergences in policy. Even in the relatively calmer period since 2000, the Bank of Canada and the Fed have often been as much as 100 bps apart on policy rates (compared with the current spread of just over 30 bps). So, yes, there is plenty of precedent for the Bank to go its own way.

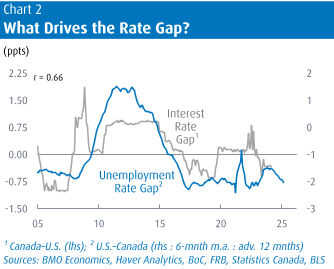

- Not surprisingly, a divergence in economic performance has driven past monetary policy divergences. This can be neatly captured by simply looking at the unemployment rate gap between the U.S. and Canada. It currently stands at -2.3 percentage points (3.8% vs 6.1%), notably wider than the -1 ppt norm of the past two decades. The gap acts as a very good leading indicator for relative monetary policy (Chart 2). The current jobless gap is consistent with Canadian short-term rates being more than 75 bps lower than their U.S. counterparts.

- The exchange rate is, naturally, the limiter on just how far the Bank of Canada can deviate from the Fed. The Bank can’t cut at will without risking a serious slide, which could easily move far beyond fundamentals and re-aggravate inflation. And, the currency market is famous for overshooting. Yet while the currency may somewhat limit the Bank’s independence, it can also reinforce the broader policy direction—that is, when the goal is to be relatively easier, a weaker loonie can amplify the effort.

- Due to global factors, the Canadian dollar is now even weaker than one would expect given just the unemployment and interest rate differentials. Put another way, the U.S. dollar is powering up against most major currencies, and the loonie’s 1.2% drop this week was not out of the norm. For example, the euro fell nearly 2% on the week, while the pound slid 1.5%.

- Given the economic conditions on the ground and the near-term outlook, the monetary policy setting between the BoC and the Fed will diverge further, with the former pivoting earlier to a looser stance.

The key question remains: By exactly how much can the BoC diverge without causing serious blowback in the currency market? Keeping in mind that the starting point is that Canadian rates are lower (5.0% overnight rate, versus 5.25%-to-5.50% for the Fed funds target), we suspect that the Bank can cut once independently, and then trim one more time—if a Fed cut appears imminent. This assumption informs our rate projection, as we have the BoC trimming rates earlier than the Fed, and one time extra this year. For both, though, we have taken out one 25 bp cut this year, driven by the persistence of sticky U.S. services inflation. We now look for three cuts from the Bank and just two from the Fed.

The timing of said cuts is data dependent. One commentator suggested this week that the Fed has become a glorified “play by play announcer” with its data dependence. We would liken them more to the official scorekeeper, tallying up all the key data points and weighting them appropriately. We have opined since late last year that the first Fed rate cut would be in July, and we are clinging to that view. Initially, that seemed very hawkish, but it now leans nearly dovish versus consensus. Given the run of heavy core CPI readings, which has lifted the 3-month trend to a meaty 4.5% annualized pace, the risks are clearly tilted to later moves. But a July cut remains a real possibility, and we will stick with it, with a follow-up cut expected only after the November election.

For the BoC, a June move is “within the realm of possibilities” says Governor Macklem, and we are sticking with that projection for now. No doubt, it will be a close call, and markets see the June meeting as a coin toss. Next Tuesday’s CPI will have a big say (we’re looking for headline inflation to tick up to 2.9%, and the cores to hold steady just above 3%), as could the federal budget on the same day. But the reality is that despite the Bank’s bold talk on independence, the U.S. data and even oil prices may have an even bigger say on the BoC’s timing of the first cut. Assuming the first cut is in June, we expect a follow-up move in July, as the Bank traditionally moves in couplets, and then one more cut late in the year. Similar to the Fed, the risks are clearly that the Bank waits longer and does less.

We would never even dream of having the temerity of saying “we told you so” on sticky U.S. inflation, but we did tell you so. It is important to drill home the point that this is now all about services inflation, and not goods. Despite the noise around energy, food and auto prices, that’s just not where the sustained price pressures are these days. Goods inflation provided the spark in 2021/22, at one point reaching 14% y/y, but it is now a mild 0.6%—which happened to be the norm in the pre-pandemic era. Services inflation took longer to get rolling, and really only peaked in early 2023 at above 7%. But just as this slow-moving beast took time to get going, it’s taking its sweet time backing off, and now sits at an uncomfortably high 5.3%, or roughly double the pre-pandemic norm.

To truly unlock this stickiness, rates will likely need to remain restrictive for an extended period. Not necessarily as restrictive as current levels, but certainly holding well above inflation. And that’s a very different world from the prior decade, which saw Fed funds below core CPI inflation from early 2008 right up until late 2018. Those were the days, my friend.

Douglas Porter is chief economist and managing director, BMO Financial Group. His weekly Talking Points memo is published by Policy Online with permission from BMO.