Fall Economic Statement: Canada’s Affordability Challenge and the Gray Rhino of a Recession

Adam Scotti image

Adam Scotti image

By Diego Flores Davalos and Kevin Page

November 16, 2023

Canadian policymakers, like those across Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, have been grappling with rising cost-of-living issues since the fall of 2021. If policy interest rates stay higher for longer to address inflation, as suggested by central bankers, this journey will likely end with a bang (economic recession) and not a whimper (growth slowdown).

This reality informs the Trudeau government’s margin of economic maneuver as Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland prepares to table her Fall Economic Statement on November 21st.

The opportunity costs of high inflation and economic uncertainty are high. There are short-term fiscal costs associated with measures to address affordability – to soften the blow of higher prices on lower income Canadians. There are long-term policy development costs related to energy transition and climate change, social priorities such as universal pharmacare and affordable housing. High interest rates and weak economies are bad for investment and government balance sheets. We need investment. We need fiscal sustainability.

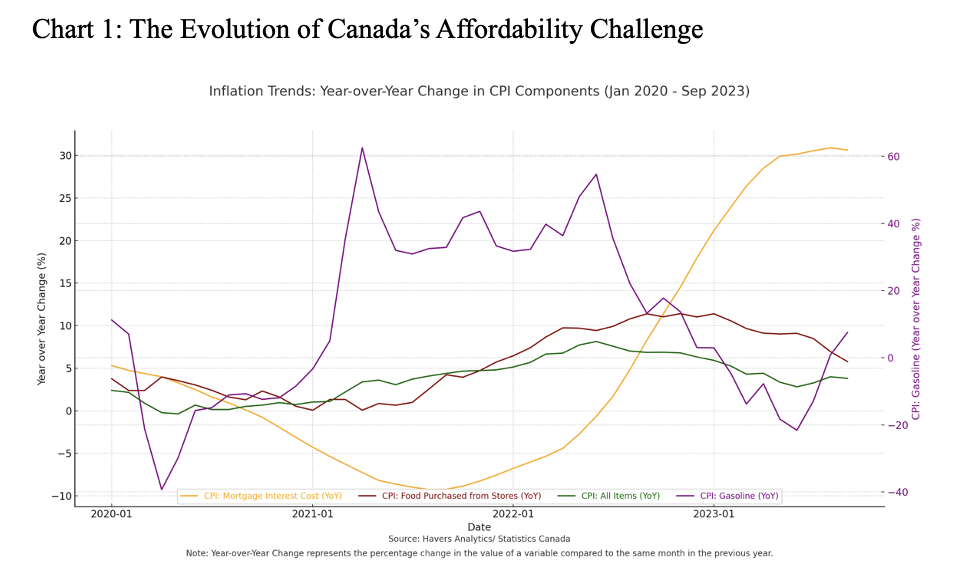

The undercurrents of Canada’s affordability challenge have evolved since 2021 (Chart1). It started with pandemic-related supply bottlenecks. Higher energy prices beget higher food prices. Higher inflation expectations drove higher core inflation. The monetary policy medicine (higher policy interest rates and less money supply growth to “cool” the economy) used in Canada and across OECD countries resulted in higher carry costs of debt, which tighten household and business balance sheets. Consumption and investment are now restrained. Growth is slowing. Unemployment is rising.

Year-over-year growth in real GDP (at basic prices) has fallen from 3.1 percent in January 2023 to 0.9 percent in August 2023. Output in the goods sector has declined for five consecutive months – a de facto sectoral technical recession. The unemployment rate rose to 5.5 percent in August – a half percentage point higher than at the start of the year. This is the historical benchmark (i.e., a half percentage point increase from its low point in the preceding year) per the Claudia Sahm rule to signal a recession in the US coined by the former Federal Reserve economist.

Year-over-year growth in real GDP (at basic prices) has fallen from 3.1 percent in January 2023 to 0.9 percent in August 2023. Output in the goods sector has declined for five consecutive months – a de facto sectoral technical recession. The unemployment rate rose to 5.5 percent in August – a half percentage point higher than at the start of the year. This is the historical benchmark (i.e., a half percentage point increase from its low point in the preceding year) per the Claudia Sahm rule to signal a recession in the US coined by the former Federal Reserve economist.

Dark economic clouds are accumulating. An economic recession is now a “gray rhino” — the “reverse-black swan” term popularized by American writer Michele Wucker to describe highly probable, high-impact yet neglected threats.

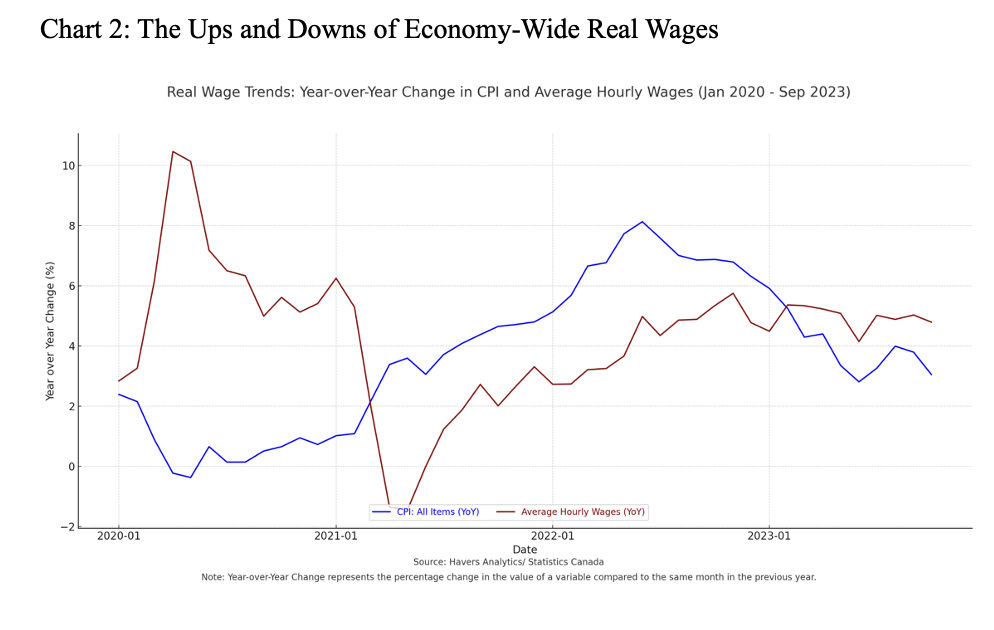

One of the reasons that economic forecasters were surprised by the resilience of the Canadian economy in late 2021 and early 2022 in the face of a nearly five percentage point increase in the Bank of Canada policy interest rate (with corresponding increases in effective household and business interest rates) was the relative strength of economy-wide real (after-inflation) wages.

One of the reasons that economic forecasters were surprised by the resilience of the Canadian economy in late 2021 and early 2022 in the face of a nearly five percentage point increase in the Bank of Canada policy interest rate (with corresponding increases in effective household and business interest rates) was the relative strength of economy-wide real (after-inflation) wages.

Chart 2 illustrates how average hourly wages far outpaced price increases during the global pandemic largely thanks to large government transfers. When price inflation rose significantly in 2021 and 22, wages fell behind. The padding of real wages during COVID bolstered household balance sheets, which supported consumption during rising inflation and interest rates.

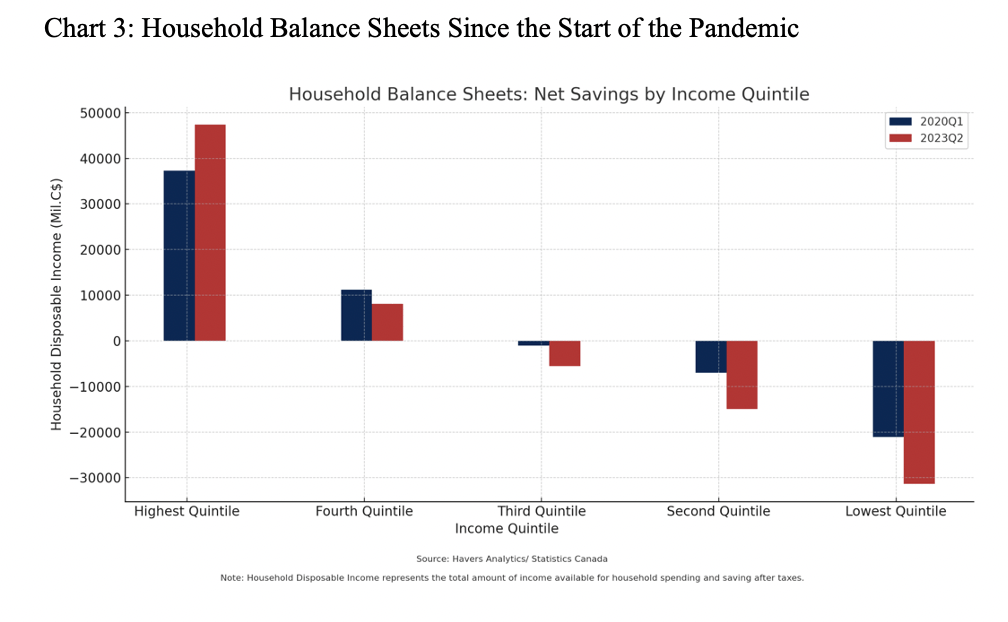

Household balance sheets are now deteriorating (Chart 3). With the exception of the highest quintile (top 20 percent) of income earners, all other income classes have experienced declines in net savings since the start of the pandemic. Notwithstanding efforts by the government to address affordability, the largest percentage declines in net savings are associated with lower income people — underscoring the degree to which the pandemic amplified economic inequality. The affordability measures (e.g., increases to GST credit, worker income, senior and housing benefits, etc) softened the blow for lower income people and supported the economy.

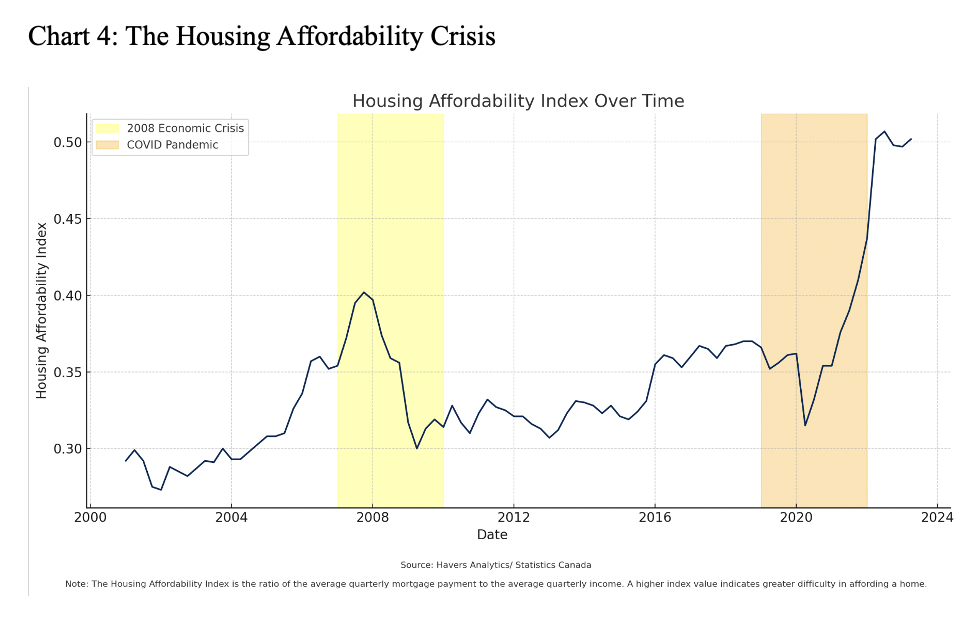

The major risk now facing domestic economic stability is likely the housing market. Mortgage interest costs as a percentage of disposable income have entered modern unprecedented territory (Chart 4). Families are struggling to manage household budgets as their mortgage rates increase. Expect ongoing weakness in consumption, especially purchases of durable goods.

The major risk now facing domestic economic stability is likely the housing market. Mortgage interest costs as a percentage of disposable income have entered modern unprecedented territory (Chart 4). Families are struggling to manage household budgets as their mortgage rates increase. Expect ongoing weakness in consumption, especially purchases of durable goods.

Where does this leave our policymakers?

We need fiscal and monetary policy to recognize the gray rhino – we are in an economic recession environment – while inflation rates remain above the target one to three percent target range. Budgetary deficits will rise modestly as a weaker economy delivers less revenue. Policy priorities to respond to affordability concerns remain. Deficit financing new long-term programs is ill-advised. Monetary policy is in the danger zone. Current high nominal and real (after inflation) interest rates are a clear and present danger to affordability and economic stability. We will need new forward guidance that allows households and businesses to plan on a return to policy interest rates at their trend level in the three percent range.

Diego Flores Davalos is a fourth-year economics student at the University of Ottawa. He is taking a research course at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD).

Kevin Page is the President of the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa, former Parliamentary Budget Officer and a Contributing Writer for Policy Magazine.