Truth vs. Illusion in a World of Chaos

Until the United Nations Secretary General addresses the real problems fuelling our ongoing parade of horribles, he will remain the Howard Cosell of new world order chaos.

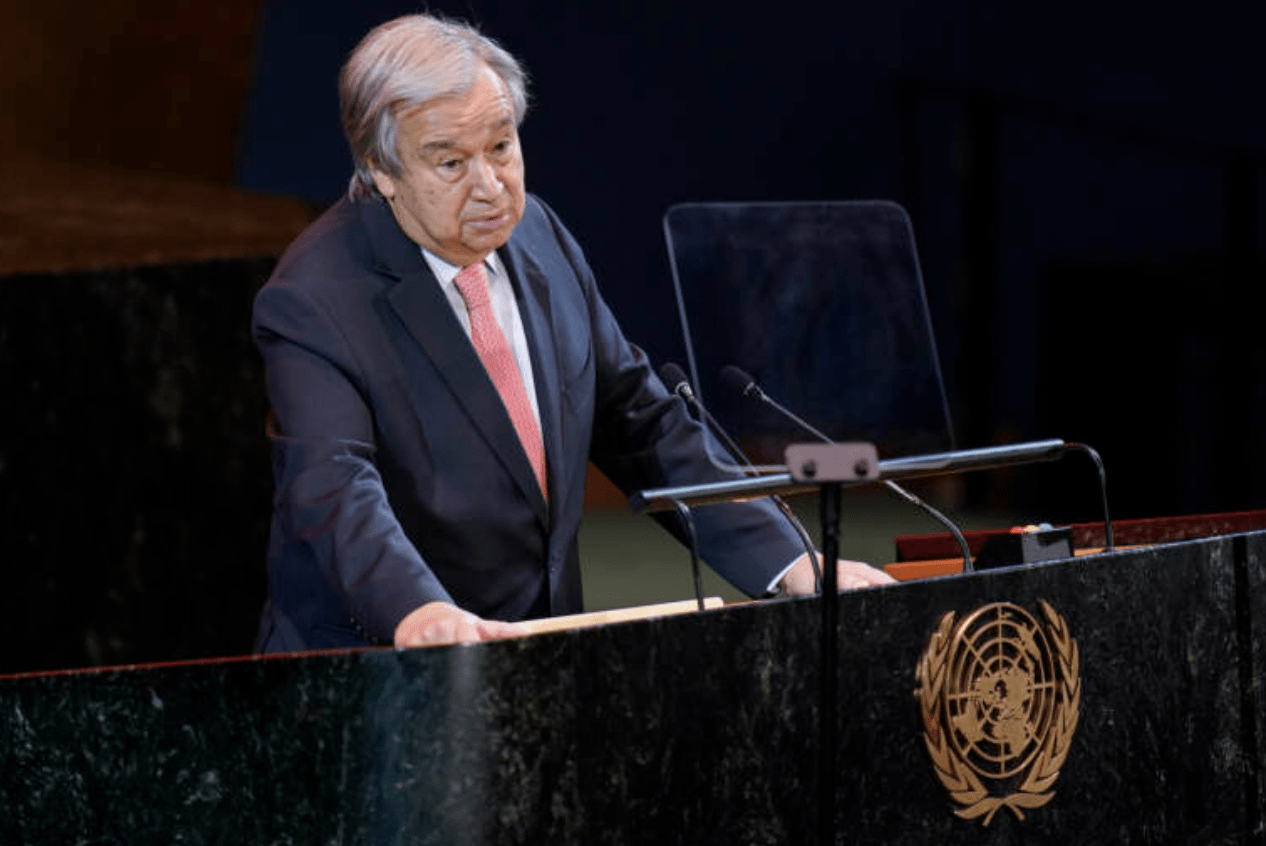

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres delivering his opening address to the 77th UN General Assembly/AP

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres delivering his opening address to the 77th UN General Assembly/AP

Lisa Van Dusen

September 20, 2022

In the days when I worked on a Washington wire desk editing White House and international news, the view above my desktop was of a collage of photo cutlines and headlines of then-United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan expressing shock, dismay, alarm, distress, anxiety, bewilderment, astonishment and other near-daily lamentations over the state of the world. The effect was one of both instant perspective and sympathy for U.N. comms writers faced with such a limited selection of synonyms for “WTF?!”

In his opening address to the 77th United Nations General Assembly on Tuesday, Secretary General Antonio Guterres, in what the Associated Press described as “an alarming assessment”, told world leaders that nations are “gridlocked in colossal global dysfunction” and are unwilling to tackle the major challenges that threaten the future of humanity and the fate of the planet. “Our world is in peril — and paralyzed,” Guterres said.

Guterres — the former Portuguese prime minister now just over a year into a second and final term as UNSG that will expire in 2026 — has been handed not a larger thesaurus through which to channel his alarm, but more catastrophizing source material than any UN secretary general since British diplomat Gladwyn Jebb first warmed the seat in 1945.

On Tuesday, Guterres cited as evidence for his distress: “The war in Ukraine, multiplying conflicts around the world, the climate emergency, the dire financial situation of developing countries, and recent reversals of progress on such U.N. goals as ending extreme poverty and providing quality education for all children,” as well as “a forest of red flags” around new technology despite its role in societal progress and connecting people.

“Let us have no illusions,” Guterres intoned. “We are in rough seas. A winter of global discontent is on the horizon. A cost of living crisis is raging, trust is crumbling, inequalities are exploding and our planet is burning…the international community is not ready or willing to tackle the big, dramatic challenges of our age.”

Just to clarify the cause-and-effect behind that assertion, the international community has indeed been a little fraught, following two decades of post-9/11, post-fourth-industrial-revolution disruption, including: 1) A power shift in the United States since 2000 away from democratic institutions to an intelligence community transformed by unprecedented financial and technological resources, 2) The economic rise of China and the leveraging of that rise as a global democracy degradation strategy, and, 3) The negative impact of both 1) and 2) on the pillars of US democracy — the executive (see 2016 presidential election), the legislature (see January 6th, 2021), the judiciary (see US Supreme Court) and the media (both social and conventional as propaganda) — through the mainstreaming of narrative warfare and strategic corruption, as well as the systematic obliteration of status-quo norms.

Beyond its supporting role in a cyclical US presidential-cycle narrative chestnut as reliable as the Iowa State Fair butter cow and the Dixville Notch recount joke, this year’s CGI positions the Clintons as part of the solution rather than part of the problem.

All of the above apply, with variations for scale and domestic political distinctions, to the international community as both a cluster of operational targets and as a synecdoche for the rules-based international order whose replacement has been the ultimate aim of so many of recent history’s weaponized wankers, dumpster fires, previously unthinkable outrages, democracy-defaming election and referendum outcomes, performative circuses, illegal invasions and other avoidable larcenies. Which leaves the current United Nations secretary general a little snookered, to put it diplomatically, in part due to the glaring truth that dysfunction really isn’t contagious, but corruption is.

As the international community’s senior diplomat, Guterres presumably would rather not refer specifically to the corrupting influence China has had on the United Nations in the past two decades — an outcome-skewing factor widely known and cited (diplomatically) by Canadian U.N. Ambassador Bob Rae in Policy magazine last October as a source of the gridlock and dysfunction to which the exasperated and appalled secretary general referred in his speech. Per Kristine Lee’s April 2020 Politico piece, China’s corrupting influence at the U.N. — which, in the hierarchy of a global war on democracy waged by covert, political and geopolitical players is mostly about division of tactical labour — has extended beyond the Manhattan landmark where Guterres delivered that speech, to multiple U.N. agencies (also see my Policy piece in our current print issue on trade, How the World Trade Organization Became a Proxy Battleground).

Meanwhile, a few ironically gridlocked blocks away at the Midtown Hilton on Tuesday, the Clinton Global Initiative was back in its UNGA-fringe slot after a six-year absence. Beyond its supporting role in a recurring US presidential-cycle narrative chestnut as reliable as the Iowa State Fair butter cow and the Dixville Notch recount joke, this year’s CGI gamely attempts to present the Clintons as part of the solution rather than part of the problem. Echoing Guterres in an AP interview, former president Bill Clinton said, “The world’s on fire in a lot of different ways, but there are a lot of things that businesses, non-governmental groups and governments working together can do to help with a lot of these problems.”

While eschewing the lazy joke about arsonists and firefighting, it may seem counterintuitive to turn for solutions to the former president whose China policy, among other fateful choices, was a key plot point of the geopolitical trajectory of the past 20 years and the former first lady whose last failed presidential bid gave America and the world the catastrophe-amplifying, big, dramatic challenge of the Trump presidency in addition to handing Joe Biden a far more onerous job than he would have had four years earlier.

Still, it is true that there are many, many things that businesses, NGOs and governments can do to solve the problems that have conspired to create the dystopian pesadelo so hair-rasingly narrated by the UN secretary general after five years of similarly alarming colour commentary. All are conditional, of course, on an end to the pathocratic power games that have fuelled the parade of horribles he presented with such incendiary, carefully curated fervour.

On a more hopeful note, Guterres said that cooperation and dialogue are the only path forward, warning that “no power or group alone can call the shots.” As understated as that admonition may sound, the man who heads what is, ostensibly, the world’s most powerful — if currently somewhat besieged —group does have a point. “Let’s work as one, as a coalition of the world, as united nations,” he added. As genuinely as someone can sound when compelled to leave out all the most important bits.

Policy Magazine Associate Editor Lisa Van Dusen was a senior writer at Maclean’s, Washington columnist for the Ottawa Citizen and Sun Media, international writer for Peter Jennings at ABC News and an editor at AP National in New York and UPI in Washington.